Zone shake down!

So you’ve read up on why heart rate is useful for training, so here is a little bit more about what’s going on with the zones, and an introduction to more of the cycling terminology.

Zones are highly personal percentages of your functional threshold power, or threshold heart rate or max heart rate. While there are many developments occurring in sports science regarding use of the ‘optimal’ training zone (critical power is becoming more accepted, however leading training software platforms haven’t yet been optimised for using these models), functional threshold power and threshold heart rate are the two we use most often, because they’re easy to use and validate and seek to represent physiological occurrences that happen at different workloads.

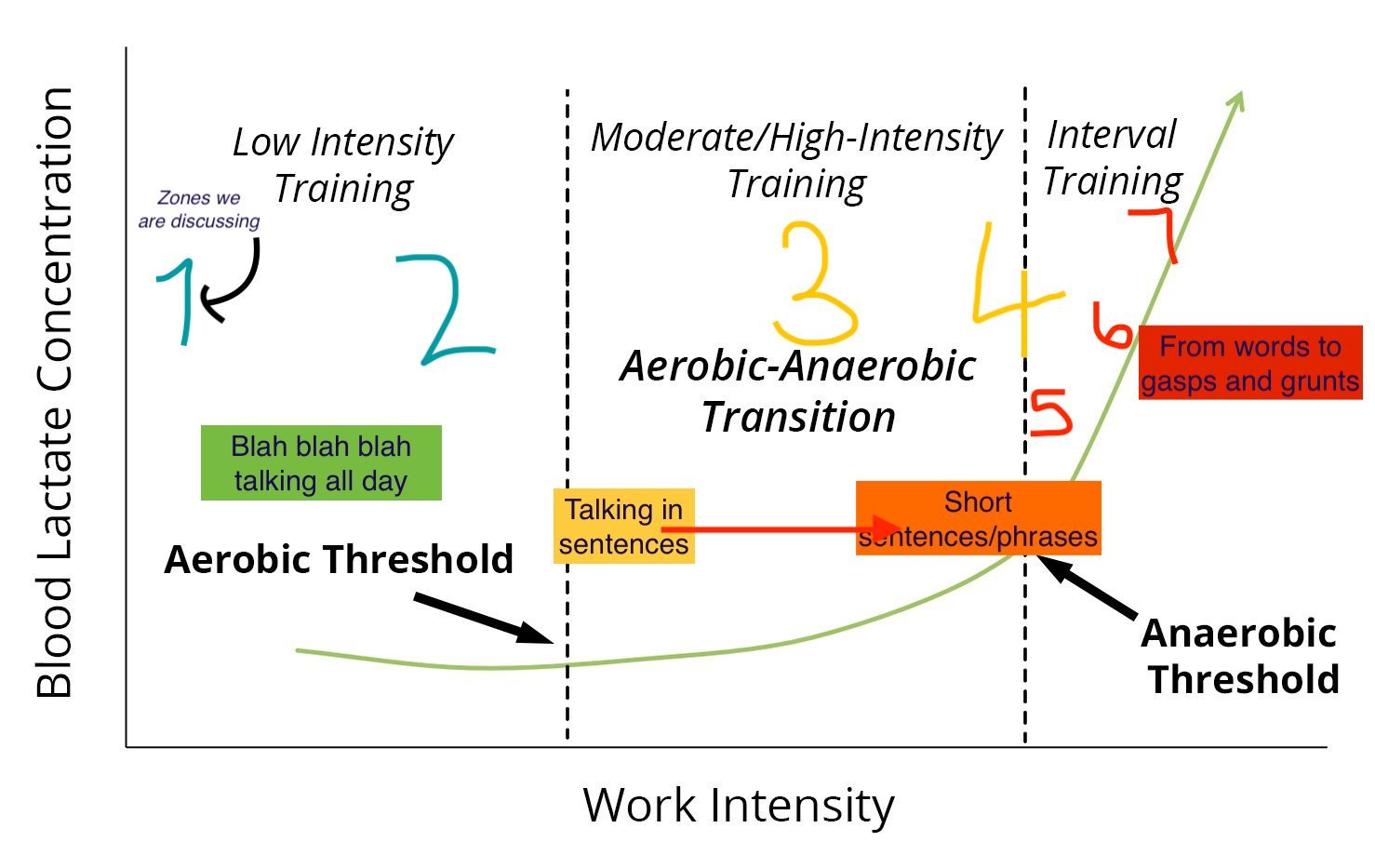

Below is a graph I have made outlining the zones and their percentages of threshold power, maximum heart rate and threshold heart rate, as well as the number this correlates to on the 1–10 scale of RPE.

The boxes marked with a * refer to efforts that aren’t easily measured by heart rate, and usually will be designated in training by maximal efforts over a certain time.

It must be noted that various sources may put zones a percentage up or down, but it’s not an absolute. Your body doesn’t go from 74-77% and suddenly be like ‘ok yes this is tempo, the changes that are occurring in this body are now completely different from the Endurance zone’. It’s a spectrum. Also, some researchers/coaches will exclusively use three zones, whereas others stick to five (or seven!), some will use zone names instead (‘endurance’, ‘tempo’ etc).

For some more basics on each zone read below.

Recovery/Zone 1: Like going for a walk, you could do this all day. You can carry out a conversation here. Focus is on recovery and restoration. Almost all type 1 (slow twitch) fibres are recruited here, and this is a wholly aerobic session.

Endurance/Zone 2: You are definitely putting pressure on the pedals, but you probably still could do this all day. Until you’re a few hours in then it starts to feel a bit more difficult! It is still for most purposes (except maybe ultra-long rides!) a very ‘easy’ zone and an aerobic effort. This zone is used as it’s a good trade-off in terms of workload that is sustainable and able to be recovered from, while still eliciting the physiologial changes like increased mitochondrial density, increased capillarisation, stroke volume, plasma volume and aerobic muscle enzyme density. Long rides in the endurance zone also builds specific substrate utilisation (using fat as a fuel source). You can have long waffling conversations with ease in the endurance zone!

Tempo/Zone 3: Tempo feels good to ride in, and is still mainly aerobic. But if you tried to do a four hour tempo ride straight away, you will certainly feel it! The slight increase in intensity can build some more pronounced aerobic adaptations than endurance training, however the trade off is that it can elicit much more fatigue, so efforts in this time should be measured. The risk factor is, as it feels pretty good to ride in tempo, that you can stretch yourself a bit too far, and the unknowingly generate more fatigue than intended. The higher portion of tempo zone, up closer to threshold, is sometimes referred to as ‘sweet spot’ and is more fatiguing than the lower part of this zone.

This zone is demarcated by the first aerobic threshold, and as such marks the point where exercise intensity shifts from wholly oxidative/aerobic, and you begin to use glycogen albeit at a rate that you are able to process without increasing accumulation. You begin to breathe a little heavier, albeit in the tempo zone you can still converse reasonably well, in sentences.

Threshold/Zone 4: Threshold is a tricky one, as there are different ways of measuring threshold all with their own limitations, and as mentioned in our Tempo explainer, tempo begins when we reach the first aerobic threshold (the one people don’t tend to talk about as much!). The threshold that is bandied around in most training talk, however, refers to the ‘anaerobic threshold’ which roughly relates (though not with precision!) to many other threshold (GXT, OBLA, MLAA, VT2…so many acronyms!). At the very basic level for the average punter, it’s the effort we can maintain for around an hour. This correlates to a further reduction in speech (usually talking in phrases), and a RPE or around 7.

Working in this zone takes a fair bit of concentration, and will take longer to recover from than more aerobic efforts.

If you have prior HR data you can use a hard race of an hour to get a good estimate.

Using maximal HR is pretty unreliable, and the old 220 minus your age, even less so.

Threshold, at its most rudimentary, represents the point after which blood lactate begins to accumulate beyond its rate of usage. The point at which this happens is what we refer to as ‘lactate threshold’ and it can be plotted looking at blood lactate inflection, time to exhaustion, and gas exchange. What this looks like is heavier breathing as a physiological mechanism to continue oxygen provision and co2 removal from the body, so speaking in phrases is probably a good indication you’re in the right spot. Power based athletes may use FTP testing (traditionally 20min minus 5–10% of average power) to set threshold, and generate zones on this, but there are limitations to this testing.

Here’s an image that I ‘upgraded’, with the two thresholds and what happens at each point. Zones here relate to the above table (1–7) and where they sit in terms of blood lactate/whats going on inside us. And how that presents (ie: breathing changes and difficulty talking)

VO2/Zone 5: Just like Threshold, VO2 falls victim of semantics, but at it’s crux it refers to the point at which maximal uptake of oxygen is reached, and efforts in this zone can be sustained (2–9min maximal!) or in on/off blocks of efforts (microburst, ie: 40 sec maximal, 20sec easy x 5). Training VO2 max elicits performance gains in aerobic performance, but if using HR it can be less precise, due to the lag in HR for shorter efforts VO2 and above).

These should be ‘very hard’ and sit at around RPE 8, and breathing here is likely down to words at best. Training in this zone results in increases in VO2 max and resulting max anaerobic power, marks the beginning of lactate tolerance training, as well as strongly affecting plasma volume and maximal cardiac output. These should be performed when some base fitness is already in place and are very stressful, so recovery is key!

Anaerobic Capacity/Zone 6: Efforts in anaerobic capacity are short: usually 30sec-2min long, and are very, very hard. No talking, only gasping! The underpinning ability to perform work in this zone is based upon being strong aerobically, so get that work done first before you hit this one up! Once again, heart rate will be a bit ‘laggy’ on this so maximal feel and/or power is the way to go.

This zone is highly glycolytic, using primarily glucose as fuel. The problem is, because of the byproducts generated and the severe domain being in excess of what our aerobic system can use, we can only work in this zone for a short time due to metabolic byproducts (namely lactate!).

Neuromuscular/Zone 7: The Neuromuscular or ‘sprint’ zone is what you see being unleashed in the closing seconds of a Tour de France flat stage: all out, teeth gritting watts and maximal exertion. This zone uses the phosphocreatine (ATP-CP) system which exhausts quickly, and as such efforts in this zone are very short, explosive and take several minutes to recover from as the body replenishes these stores. Unlike the anaerobic system, the neuromuscular system relates to that short, sprint power that is alactic: that is, it is short enough that it doesn’t generate lactate (however if you keep a sprint going for longer than 20-ish seconds you will begin to move into the anaerobic zone!). As such, short bursts in this zone almost don’t even hurt until the end….weird?!

Generating good output in this zone is a bit of alchemy of timing, coordination, technique and balls to the wall grunt. These are too short for HR based training!