Training basics for new and not-so-new riders

If you’re new to cycling training, there are a whole lot of terms and jargon to get your head around. TSS, CTL, IF, watts, power-to-weight. These are all concepts that are applicable to cycling training, but sometimes getting stuck on these terms means you can’t see the forest for the trees.

At its very core, training can be broken down into a few concepts which we will outline here, and explain the reasons behind why your program is structured in the manner it is. After all, if we understand the reasons why something is the way it is, we are more likely to ‘buy in’ and be compliant, knowing that the outcome is based on complying with the training process.

This article is deliberately talking about the forest: the concepts that underpin successful training programs, and doesn’t delve deeply into energy systems and acronyms on purpose: before you go down that rabbit hole, read this to understand the context in which the cycling-specific jargon and terminology exists.

Progressive Overload and Adaption

“Do more of the thing to get better at the thing”

The first principle of training is progressive overload and adaption. This is the concept that in order to progress, we seek a series of adaptation in energy systems, which result in us having stronger endurance, and better power production across durations.

With gradually increased volume, our body undergoes structural changes to make us better at cycling, and different intensities elicit different structural changes. The basis of cycling endurance disciplines (road, track endurance, mountain biking) is aerobic conditioning, and as such steady ‘easy’ aerobic riding makes up a large part of an effective training plan.

Volume can be increased by: increasing ride duration OR increasing riding frequency, or a mixture of both depending on the athlete.

Intensity also plays into the progressive overload mix: it’s going to be difficult to go super hard in an event without any hard rides or efforts. By adding intensity gradually, we work on different energy systems that support aerobic capacity, or short and sharp work that supports our anaerobic capacity (think sprinting up a hill <90 sec or a sprint at the end of the tour!). We keep check of how much load and volume we add: it’s important to keep volume addition reasonably conservative to reduce the chance of overtraining.

Without getting into the nitty gritty, here is a graph and after a bit of a plateau (the athlete had a break) it goes upwards. This indicates training volume is increasing at a steady and sustainable rate!

2. Variation

“Jazz up the thing to work improve different aspects of the thing”

While aerobic endurance training (riding for a long while at an easy pace) is a mainstay of aerobic conditioning, if that’s all you did leading into an event you would lack key physiological qualities that are developed by riding at different intensities. Likewise if you always ride on flat terrain but your ride/race/event features some hills, you will struggle.

Variation is a key concept in training, not just to train the appropriate energy systems that make us faster and stronger, but also in terms of developing other parts of ourselves as a cyclist, including riding different terrain, increasing riding skill and confidence (riding in a bunch, riding on road or on trails), and the many mental benefits of variety.

3. Specificity

“Work on the aspects of the thing that are specific to the thing”

A core part of training is Specificity: in that the demands of the event targeted must be developed specifically in training. For a road cyclist, this can be breaking down the demands of a specific race and looking for the selective parts of the race and what physiological capacities are needed to do well (ie: if it’s likely a sprint, sprint training is key, but also the positioning to get to that point. A decisive 5min climb? Maximal aerobic power may be the deciding factor!).

Generally, the way training is structured is from general training and addressing obvious limiters, moving towards more specific training closer to your goal event!

Specific training for your event may include becoming comfortable riding in a tight group/bunch skills, as well as specifically addressing the physiological requirements of your sport!

4. Reversibility

“Stop doing the thing and you’ll get worse at the thing”

Just as we progressively overload to become fitter, faster and stronger, a lapse in training will result in a period of detraining. This is the principle of reversibility: the changes we train for can be reversed by ceasing training.

Generally, professional athletes and those with year-round structure have training ‘breaks’ at least once a year, and reversibility is part and parcel of that. Without a break in training at some stage, it’s likely the athlete will become tired and stale. However, we must sacrifice some fitness here in order to recover from the overall stress of a cumulative season of training, in order to rebuild better and faster for the next season.

5. Recovery

“Do the thing, then have a break to recover from the thing, to ultimately make you better at the thing”

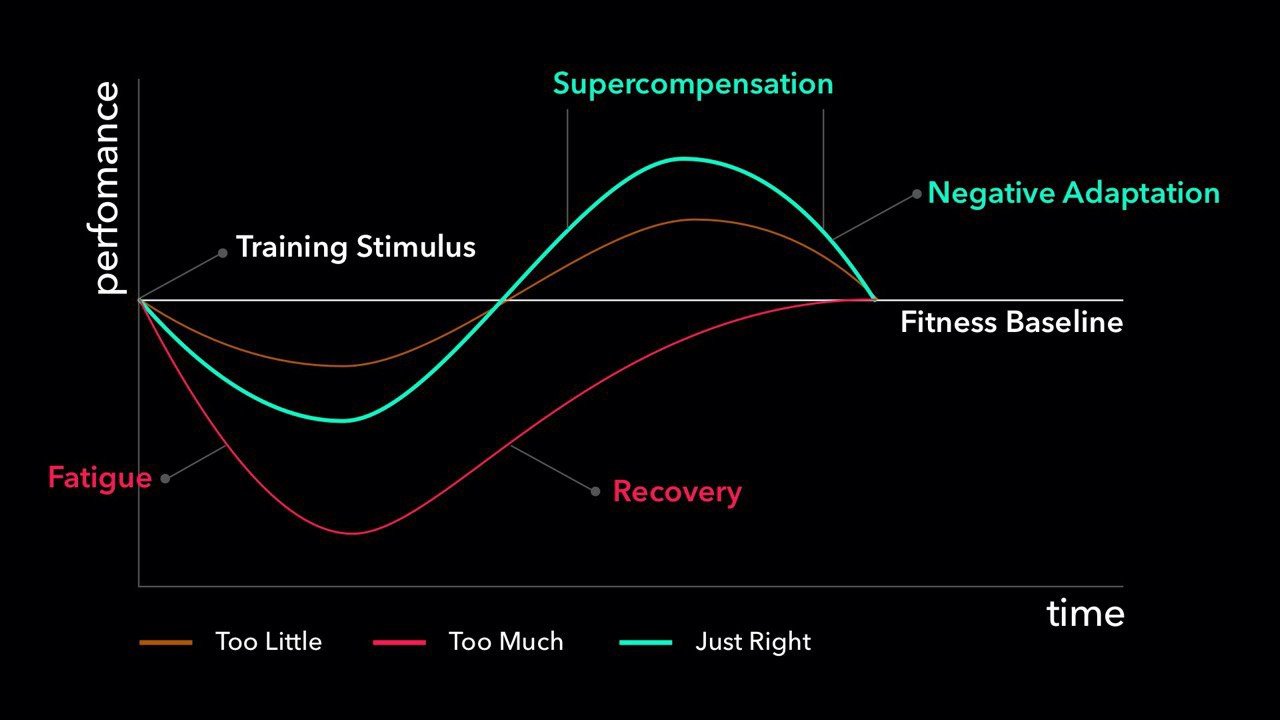

While overload is key to building a better cycling engine, recovery is the yin to this yang. While we stress the body in training and tactically build some fatigue, periods of recovery allow for the changes to take place in a process we call ‘supercompensation’. When we get our load and recovery right, we have returned fitness gains (see green line on image below). If we train too hard without adequate recovery, we dig a hole of fatigue and fail to see fitness gains (red line). If we train pretty well, but then recover for too long, or don’t stress our body enough through training, we experience reversibility and stasis or lack of progression (yellow line).

Key elements of recovery include time off or easy days, adequate sleep, stress reduction, relaxation, hydration and nutritional adequacy. While there are many cool recovery ‘tools’ and nutrition you can purchase that are purported to expedite the recovery process, without the basics it’s almost pointless to spend money on these. Focus on the big, key things before considering the one-percenters.

6. Individuality

“How you do the thing depends on you"

As they say, there are many ways to skin a cat. But animal cruelty aside, cycling training, in order to be successful, needs to fit with you. This means, training when you can, using your local topography, creating rides that are conducive to your success.

Commuting, for those not WFH, is a great way to add purpose and volume into your weekly training. Or perhaps you have a friend or social group to ride with? Incorporating things that you look forward to (even within an existing training program!) is key to keeping you pedalling happily along.

Some ways I like to individualise my own/others training:

-Completing some training in social rides with others, where the group goals are similar

-Using training and cycling as a mode of transport to ‘get somewhere’ (work/appointments etc).

-Using opportunities to ride in new places as mini-breaks from life stressors

-Using small blocks of time <1hr on the trainer at home if time-crunched

-Creating jazzy ride routes using software such as ridewithgps.com to explore local areas

-Changing up the ride purpose frequently (MTB skills, hill training, long endurance training)

-Completing hard efforts or specific sessions on nearby terrain that can facilitate this (ie: medium climb on MT Coot-tha, sprint training on quiet country roads etc)

Incorporating favourite locations and adventures can be key in individualising your training.

7. Other puzzle pieces

“There are many parts of the thing”

While we have mainly talked about the principles of training as relating to eliciting physiological changes that make us better at riding bikes, there are many other pieces of the puzzle to becoming a better athlete. Key concepts such as general nutrition and sports nutrition play a key role in fuelling workouts and recovering (remembering that’s where the adaption happens!), as well as mental toughness and motivation, and having the right support crew around you. Access to good training ground (roads, bike paths, hills, flats, indoor trainer, trails, whatever it is that sets you up for success) is also key in training outcomes.